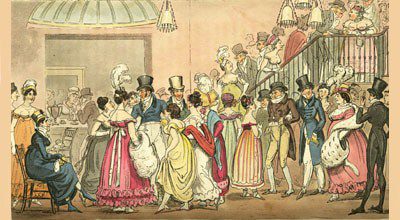

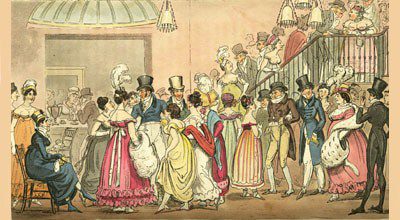

Being a lady during the Regency Era was a very special, very difficult and very demanding role. There were certain things expected from the girl’s side that affected her social status. Her deeds and behavior had an impact on her family—mostly on her father and her husband.

A lady’s reputation was based on her behavior but also on her appearance. The classic phrase “Caesar’s wife must be above suspicion” was a basic rule for ladies of the time.

In this article I will talk about the most important five rules that a lady who lived in England during the Regency Era was obliged to follow.

During the era, the basic rule for the appearance of a lady was, as far as we know, a complicated and strange combination of female weakness, but also the dynamics of a mother. So every lady would have to look sweet, weak, in need of protection but—at the same time—strong, and someone who was capable of showing harsh affection and love.

This was first and foremost translated into correct posture: people of the era were obsessed with it. A lady would have to stand upright and, even when sitting, her shoulders would have to be straight back. Her movements ought to be more feminine, more tender, more elegant.

Of course, a lady‘s femininity and weakness were also used as a weapon, whenever needed. For example, if a lady was under pressure, she could easily use behaviors such as hysterical outbursts and fainting, as a way for her to avoid unpleasant circumstances.

When a lady was confronted with foul language or bad manners, she was supposed to faint. Such shows of weakness were considered an appropriate reaction from women during the era.

In reality, however, Regency women were not so overly sensitive and subtle. But it was considered appropriate for them to pretend to be weak, to allow men to treat them as proper ladies.

A lady’s reputation and social status required her to be the definition of femininity. She was obliged to look and be prudent. A lady was to behave with ‘courteous dignity’ at all times.

In an obscene comment or in the view of a scene of violence, proper ladies were expected to be shocked. A lady should never be seen standing and talking on the street. Or to be seen talking to a man without a chaperone. Or to gossip in public. As you can imagine, just walking down a busy street could be a social etiquette minefield!

When it came to interacting with the opposite sex, the rules for the ladies were absolutely prohibited.

If a lady was unmarried and under the age of thirty (30), it was not allowed for her to be seen in the company of a man without having a chaperone. A chaperone would ensure that the lady’s reputation would not be tarnished, either by indiscreet eyes or by vulgar conversations with her companion.

A chaperone could be another lady, an appropriate man, or a servant. If the lady’s reputation was somewhat tarnished, it would indicate that the chaperone was unable to protect her and it would automatically ruin the reputation of the lady’s entire family. There were only two occasions where this unwritten rule could be overseen: a walk to the church or to a park, during the early morning hours.

Every person who wanted to socialize with other people needed to be introduced and introduce someone back. As in every other aspect of everyday life, there were some rules that had to be followed.

The need for formal introductions was another way for women’s reputations to be protected. A lady could not, for any reason, be introduced to someone arbitrarily and without a mediator. Usually, introductions were made by the ‘man of the house’ and once he made the appropriate introductions, the ladies in his household could socialize with their new acquaintances.

As a rule for an introduction, both parties ought to give their permission. This was even more absolute when it was a matter of hierarchy. When a person was of higher social status than the other, then they had to give their consent to have strangers be introduced to them, otherwise it would be considered a scandal.

Even more, a lady was forbidden to speak to another person—especially to another man—with intimacy. At no point could a lady address a gentleman by his first name. Instead, she would call him by his surname, or his title.

Finally, there was the act of bowing during the introduction between two people. The lady was expected to bow, slightly with her shoulders, while a gentleman was expected to greet a lady with a modest, not exaggerated, bow coming from the waist.

In my next article I will write about the other five rules of Etiquette that a girl had to follow in order for her to become a Lady during our favorite Regency period.

Until then, please let me know your thoughts about this article!

For what do we live, but to make sport for our neighbors, and laugh at them in our turn?

-Mr. Bennet, Pride and Prejudice

Written by Scarlett Osborne