Hi there my darlings!Have you ever wondered where all our great freedoms and rights as women started from?

I know the world isn’t perfect on this issue yet, and we are still working on equality, but things used to be much worse, and not as long ago as you might imagine!Let’s take a look!

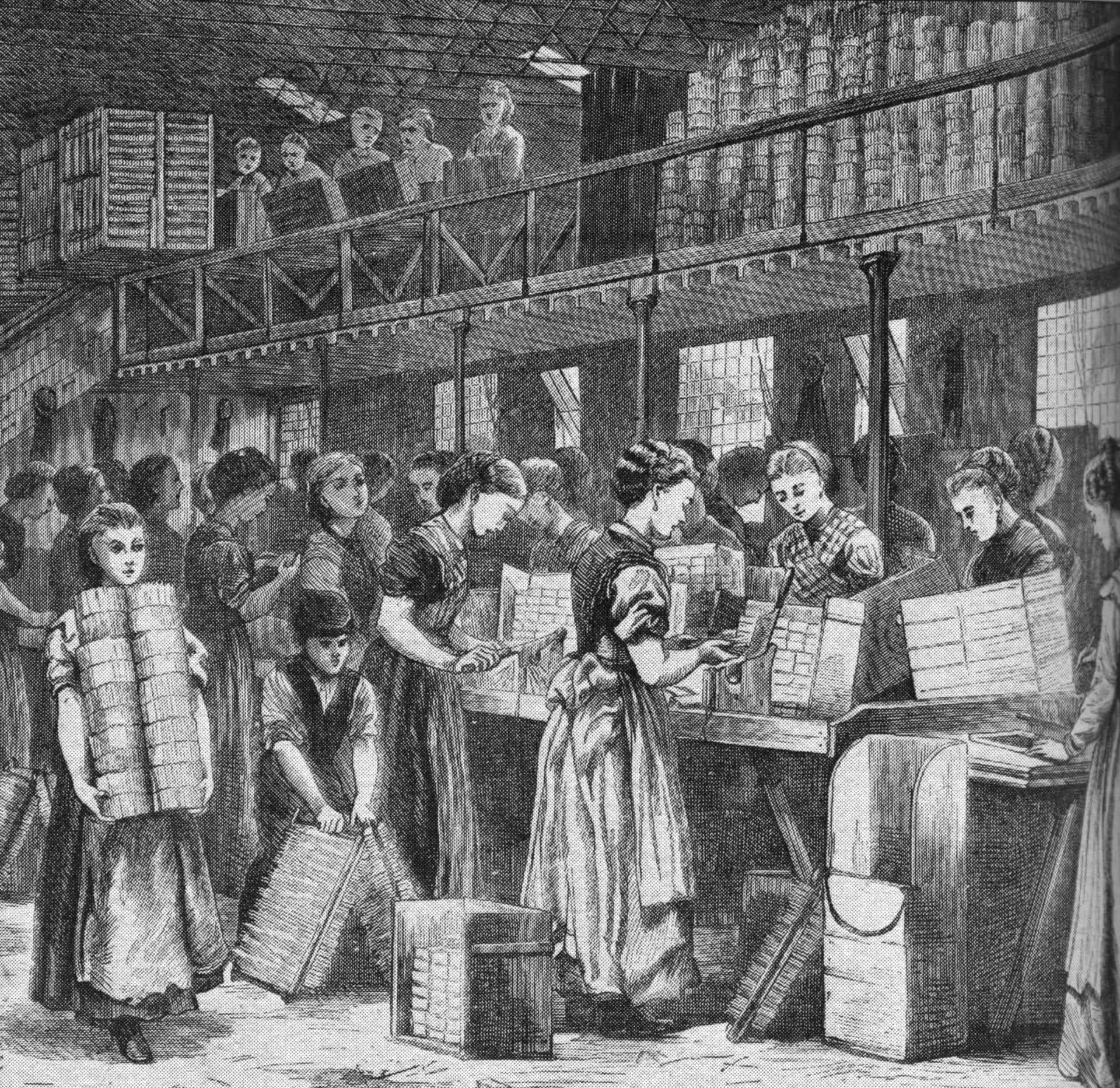

Most working class women in Victorian England had no choice but to work in order to help support their families.

They worked either in factories, or in domestic service for richer households or in family businesses. Many women also carried out home-based work such as finishing garments and shoes for factories, laundry, or preparation of snacks to sell in the market or streets.

This was in addition to their unpaid work at home which included cooking, cleaning, child care and often keeping small animals and growing vegetables and fruit to help feed their families.However, women’s work has not always been accurately recorded within sources that historians rely on, due to much of women’s work being irregular, home-based or within a family-run business. Women’s work was often not included within statistics on waged work in official records, altering our perspective on the work women undertook.

Often women’s wages were thought of as secondary earnings and less important than men’s wages even though they were crucial to the family’s survival. This is why the census returns from the early years of the 19th century often show a blank space under the occupation column against women’s names – even though we now have evidence from a variety of sources, from the 1850’s and on, that women engaged in a wide variety of waged work in the UK.

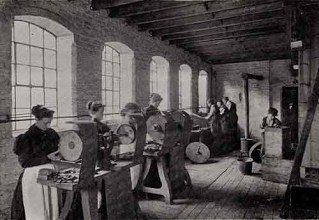

Women’s occupations during the second half of the 19th and early 20th century included work in textiles and clothing factories and workshops as well as in coal and tin mines, working in commerce, and on farms. According to the 1911 census, domestic service was the largest employer of women and girls, with 28% of all employed women (1.35 million women) in England and Wales engaged in domestic service. Many women were employed in small industries like shirt making, nail making, chain making and shoe stitching. These were known as ‘sweated industries’ because the working hours were long and pay was very low . Factories organised work along the lines of gender – with men performing the supervisory roles and work which was categorized as ‘skilled’.Throughout most of this period women were paid less than their male counterparts working alongside them, which created great financial difficulties for working women. From the 1850’s an on, trade unions began to be established, first among better paid workers and they then expanded to represent a wider range of workers. However, women remained for the most part excluded from trade unions, and unequal pay was the norm. In many cases, women attempted to demand better rights and some were supported by social reformers.In 1888 Clementina Black, one of the only 2 women delegates at the Women’s Trades Union Council, proposed the first TUC equal pay resolution. This demand was made not on the basis of women’s right to equal pay, but on the basis that their lower pay disadvantaged men in the labor market. The resolution stated that where women were “employed merely because they were cheaper, all work gradually fell into their hands, … and that this resulted in lower (wages) to the general injury of men and women alike.” But it took many decades for this demand to be supported by the wider union movement.

The majority of upper and most middle class women did not undertake paid work except for ‘respectable’ activities like being a governess or a music teacher or even a nurse. Most women of this class were expected just to get married and look after their children and home. Professional jobs like lawyers, vets, civil servants remained closed to women through much of the 19th century.Byrant and May match factory strike (1888)One of the most famous strikes by women workers during the nineteenth century took place during the exceptionally cold July of 1888 at Byrant and May match factory in the East End of London. The strike began when 200 workers left work in protest when the factory owners sacked three workers who had spoken to a social reformer, Annie Besant, about their working conditions.Besant published an article in her halfpenny weekly paper “The Link” on 23 June 1888, entitled “White Slavery in London”. This article about the conditions at the Byrant and May factory highlighted fourteen-hour work days, poor pay of between 4-8 shillings a week, excessive fines and the severe health complications from working with white phosphorus.According to Besant:“The hour for commencing work is 6.30 in summer and 8 in winter; work concludes at 6 p.m.

Half-an-hour is allowed for breakfast and an hour for dinner. This long day of work is performed by young girls, who have to stand the whole of the time.

A typical case is that of a girl of 16, a piece-worker; she earns 4s. a week. Out of the earnings, 2s. is paid for the rent of one room; the child lives on only bread-and-butter and tea, alike for breakfast and dinner, but related with dancing eyes that once a month she went to a meal where “you get coffee, and bread and butter, and jam, and marmalade, and lots of it.

The splendid salary of 4s. is subject to deductions in the shape of fines; if the feet are dirty, or the ground under the bench is left untidy, a fine of 3d. is inflicted; for putting “burnts” – matches that have caught fire during the work.”

The strike register shows that many of the workers had Irish names and lived in close proximity to each other. The workers organized themselves in the face of intimidation from the factory owners and took their campaign to parliament. They got some support from the London Trades Council and after three weeks on strike, Byrant and May met all their demands. Subsequently, the Union of Women Match Workers was formed by the workers.What do you think about that? Women making history! But maybe things aren’t all that better yet, at least not everywhere in the world. So let’s speak up and speak out, women supporting women!

Written byEmma Linfield!

Share this book

Share this book